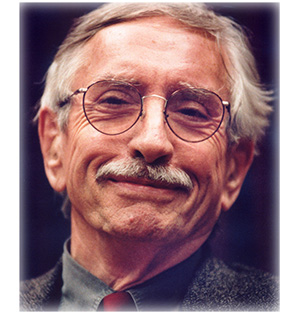

The following Biography was written by Lincoln Konkle, a founding member of the Society and Professor of English at The College of New Jersey.

Edward Albee was given up for adoption shortly after his birth March 12, 1928 in Washington D.C. Although Albee knew he was adopted by the age of six, and therein lay the beginning of his alienation, he only learned the few details of the circumstances of his birth and adoption after his adoptive mother’s death in 1989: his biological father abandoned his mother Louise Harvey and she gave up her son Edward Harvey to an adoption agency two weeks after his birth. Reed and Frances Albee became his foster parents, bringing him to their home in Larchmont, New York when he was only 18 days old; they officially adopted him on February 1, 1929, and changed his name to Edward Franklin Albee III.

Edward Albee was given up for adoption shortly after his birth March 12, 1928 in Washington D.C. Although Albee knew he was adopted by the age of six, and therein lay the beginning of his alienation, he only learned the few details of the circumstances of his birth and adoption after his adoptive mother’s death in 1989: his biological father abandoned his mother Louise Harvey and she gave up her son Edward Harvey to an adoption agency two weeks after his birth. Reed and Frances Albee became his foster parents, bringing him to their home in Larchmont, New York when he was only 18 days old; they officially adopted him on February 1, 1929, and changed his name to Edward Franklin Albee III.

The Albee’s were an old American family, having immigrated to Maine in the seventeenth century; an ancestor was one of the original minutemen in the Revolutionary War. Albee’s grandfather, Edward Franklin Albee II (1857-1930), was co-founder and partner with B.F. Keith in a chain of vaudeville theaters located throughout the U.S. Consisting of over 400 theaters, the Keith-Albee circuit, which later merged with other theaters to form RKO (the Radio-Keith-Orpheum Corporation), made the elder Albee millions, subsequently inherited by his son. Reed Albee was the rich-man’s son-type; he worked as an assistant general manager in the company until he retired the year he and his wife adopted their son. Reed had married Frances Cotter in 1925, a year after his first marriage of ten years ended in divorce; it was the first marriage for “Frankie,” who was twelve years younger than Reed. She was tall and imposing, he short and dapper. He bought thoroughbred horses for showing, she rode them and won the ribbons. Frances was working in a department store in Manhattan when she and Reed met; she came from a family of upstate New York farmers that apparently were not a significant part of young Edward Albee’s life, except for his grandmother, who eventually came to live with the Albee’s.

In his own estimation, Albee did not have the kind of carefree, nurtured childhood one hopes for every child growing up. His mother was emotionally cold and domineering; his father was distant and uninvolved in his son’s rearing. Albee’s closest adult relationships were to his nanny, Anita Church, and to Grandmother Cotter. The affluence of his family did expose him to culture: his nanny introduced him to opera and classical music; the library in the Albees’ large Tudor house contained the classics of world literature (though Edward was scolded for removing the volumes which were intended for show and not actual reading); he was driven in a limousine to see Broadway productions deemed appropriate for his age (for example, Jumbo with Jimmy Durante, Rodgers and Hart’s On Your Toes, and Hellzapoppin’); and famous actors and other entertainers such as Ed Wynn were frequent guests in his parents’ home. The Reeds were nouveau riche in an upper-class neighborhood in Larchmont, which is in Westchester County, New York; they were members of the country club and the yacht club, and they had servants. Albee has said that he was in rebellion against their snobbery and prejudice early on, and would later satirize these traits in characters that resembled his adoptive parents socioeconomically as well as psychologically. His unhappiness as a child was evidenced by his expulsion from three private preparatory schools: Rye Day School in New York, the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey, and Valley Forge Military Academy in Pennsylvania. However, he found his niche at Choate in Wallingford, Connecticut where he wrote a play, a novel, poems, and short stories in the manner of those published in The New Yorker, an early inspiration (especially the work of James Thurber). Some of these juvenilia were published in the school literary magazine and one poem was published in a Texas literary magazine in 1945. Albee has said that he decided he was a writer as a young child; his teachers at Choate encouraged him in that pursuit. Upon graduation, he matriculated to Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, where he published in the literary magazine and acted in a couple of plays, but was expelled in his second year for not attending required courses and chapel. In that same year he left home (or was thrown out) after a fight over his late night drinking, which ceased all contact between him and his adoptive parents for twenty years.

Albee spent the 1950s living in Greenwich Village in a number of apartments and working a variety of odd jobs (for example, a telegram delivery person) to supplement his monthly stipend from a trust fund left for him by his paternal grandmother. He met and became involved with William Flanagan, who had come east from Detroit to study music and was the music critic for the Herald Tribune and other publications. In 1952 Albee moved in with Flanagan, his first long-term gay relationship. Although he had had a few heterosexual experiences, had even been unofficially engaged to a socialite whose parents were friends of his parents, Albee had also had gay experiences as early as age 13, and frequented gay bars while he was in college. Flanagan was, however, more than a lover to the young Albee; he was also an artistic and intellectual mentor. He was the leader of a group of young composers and musicians who socialized together and sometimes with painters, sculptors, and other artistic persons in the Village who were part of the various avant-garde movements. According to Albee’s biographer Mel Gussow, Greenwich Village in the Fifties was like Paris in the Twenties when Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and other writers and artists and intellectuals lived, wrote, and socialized on the Left Bank. Flanagan and his entourage, of which the only writer was Albee, attended the theatre, art exhibits, and other cultural events, as well as frequenting lower Manhattan nightspots. During this time Albee saw Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh and T.S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party on Broadway. Thus, in his twenties Albee experienced the equivalent and perhaps even better of a college and graduate school education.

In his early adulthood, Albee was still bent on becoming a writer, though not making much progress. On his first trip abroad to Italy and France with Flanagan, he searched for inspiration and wrote a great deal, but nothing came to fruition. He submitted to The New Yorker but was rejected. Over a ten-year period, Albee wrote, according to Gussow, “nine plays, dozens of stories, and more than 100 poems,” none of which were published or produced. During the early part of the Fifties he was concentrating on poetry, but after showing his poems first to W.H. Auden and then to Thornton Wilder, whose Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth he had seen on Broadway, Albee took Wilder’s advice and started writing plays, of which a few survive in manuscript. The two scholars who have read these apprentice plays and commented upon them in print have agreed with Albee that they lack his distinctive voice, especially his sense of humor, which was first heard in The Zoo Story in 1958. The famous story of how Albee wrote what was to be his first produced play has him approaching his thirtieth birthday with a sense of desperation that he would never be a writer. Thus, he “liberated” a typewriter from the Western Union office where he worked and wrote The Zoo Story (which for years he claimed was his first play) in three weeks as a birthday present to himself. Although it took some time to get it on the stage, both Albee and Flanagan knew that he had taken a giant step forward. Gussow reports that upon listening to a staged reading of The Zoo Story at the Actors Studio, novelist Norman Mailer stood up and proclaimed it the best one-act play he had ever seen.

The Zoo Story was initially staged in 1959 in Berlin with German actors speaking a German translation of Albee’s dialogue. Critics’ reaction to this first production and the subsequent American premiere in 1960 were mostly positive, but as Albee himself has noted for years and Gussow’s biography confirms, his plays have always received mixed reviews, rather than the usual description of his career as going from universal acclaim for early works to progressive condemnation for later ones. The Zoo Story was a critical and commercial success and launched Albee’s career as a professional playwright in spectacular fashion: it won him the Obie (the Off-Broadway equivalent of the Tony award) and other awards; got him an agent at William Morris by whom he is still represented; partnered him with his longtime producer Richard Barr; and earned him fame if not fortune, the latter coming with the enormous commercial success of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

In Albee’s personal life, right before he left for the German premiere of The Zoo Story, he and Flanagan separated, and soon after his return from Europe he began living with Terrence McNally, a young actor who was later to become a famous playwright himself. While he was abroad Albee saw plays by Bertolt Brecht, Jean Genet, and Brendan Behan. His grandmother Cotter died at age 83 before The Zoo Story was produced in New York; he later dedicated The Sandbox to her. Now that he was financially secure, having received the one-hundred-thousand-dollar principal of the trust fund left for him by his paternal grandmother when he turned 30, Albee no longer needed to work odd jobs and could write full time. His second play, The Death of Bessie Smith, was another one act, the inspiration of which was the back-of-an-album-cover description of the circumstances of the famous blues singer’s death. Like The Zoo Story, The Death of Bessie Smith premiered in Germany in 1960, then in the U.S. in 1961; it was not as well received by critics as The Zoo Story, nor have scholars regarded it as a successful work.

1960 was a watershed year for Albee, having three plays performed in New York: The Zoo Story, The Sandbox, and Fam and Yam; a fourth, The American Dream, would be mounted in the first month of 1961, and a fifth, The Death of Bessie Smith, by March. This surely fits the description, “taking the place by storm.” Fam and Yam was published in the September 1960 issue of Harper’s Bazaar before being staged first in Connecticut and then in New York.

Albee’s next project after The Death of Bessie Smith was The American Dream which, according to Gussow, was a reconceptualization of The Dispossessed, one of his apprentice plays from the Fifties. While working on The American Dream he received a commission from a festival in Spoletto, Italy to write a short play; rather than begin something new, Albee excerpted four of the characters from The American Dream, putting them in a different setting and circumstances; the result was The Sandbox. This would appear to be the origin of Albee’s composing process: he thinks about a play over a period of time (sometimes years), and when he is able to imagine the characters in a situation different from the one in the play he is working on and can predict what they would say and do, he knows he is ready to begin writing.

Though The Sandbox did not have a long run, the following year it was performed on television with plays by Beckett and Ionesco, again associating him with the Theatre of the Absurd. The Sandbox incorporated music by Flanagan written especially for the piece, which was his and Albee’s second collaboration; their first, a song with lyrics by Albee and music by Flanagan, had been performed in Carnegie Hall in 1959. Their third collaboration was the opera Bartleby, adapted from Herman Melville’s short story “Bartleby the Scrivener” with music by Flanagan and libretto by Albee. Bartleby was initially paired with The American Dream, but it was so poorly received that the producers quickly replaced it with a dance piece until the first American production of The Death of Bessie Smith could be mounted to play with The American Dream. The American Dream was the first play staged by the production team that became Albee’s favorite: Richard Barr and Clinton Wilder producing and Alan Schneider directing. The American Dream opened in January 1961 and enjoyed a healthy 370-performance run, and would often be revived along with various combinations of the other three early one-act plays. Riding the swell of the success of 1960 and early 1961, Albee went on a cultural exchange program to South America, along with the production of The Zoo Story, which was actually assailed on the floor of the Senate as filthy, not the last time an Albee play was branded with that label. While he was in Brazil, Reed Albee, his adoptive father, died; Albee did not attend the funeral. Upon his return to the States, he continued writing his first full-length play that he had begun working on the previous year; Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was finished by January 1962. As with his one acts, there was praise from readers for the new work in manuscript but it did not immediately find a theatre and the backing to stage it.

Although Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is now canonized as one of the greatest American plays ever written, the critics’ reviews were mixed; that is, they were generally either all praise or all pan, with few in between. It won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for best play and five of the six Tony awards for which it was nominated: best play, production, director (Alan Schneider), actor (Arthur Hill), and actress (Uta Hagen). It was denied the Pulitzer Prize, however, because the board of directors did not want to give the award to a “dirty” play. John Gassner and John Mason Brown, the widely respected drama critics who recommended Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? for the prize, resigned from the Pulitzer committee in protest, and no award in drama was given that year. However, the play was commercially successful beyond anyone’s wildest imagination, running for 664 performances. With his earnings Albee purchased a house in Montauk on Long Island and with his producers formed “The Playwrights Unit,” a workshop that helped young playwrights by staging their early dramatic works. Over a hundred plays were produced by Barr/Clinton/Albee between 1963 and 1971, many of them by beginning playwrights who would go on to have successful careers in the theatre: Sam Shepard, John Guare, Lanford Wilson, Amiri Baraka, and others. It was also around this time that Albee started lecturing at colleges. The culmination of the hype over Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? was Albee meeting President Kennedy at the White House. Thus, he had become a FAM (though not like FAM) with his first full-length play. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? went on to even greater success when Ernest Leman adapted it for the screen, with Mike Nichols directing and starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, who won an Oscar for best actress in 1967.

Not content to rest on his laurels, in 1963 Albee wrote his next play, an adaptation of Carson McCullers’ novella The Ballad of the Sad Café. This was the first of four adaptations he would write in his career. Even with Alan Schneider directing and Colleen Dewhurst starring, the play was a failure, running for 123 performances and receiving negative reviews.

Later in 1963 Albee went on another cultural exchange, this time to the Soviet Union, paired with John Steinbeck and his wife. Visiting Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, as well as the USSR, they met with writers, painters, and university students. While in Eastern Europe, they heard President Kennedy had been assassinated. When Albee returned, he and McNally broke up and he began living with William Pennington, an interior decorator. By December of 1964 he had his second original, full-length play on the stage, Tiny Alice. Albee’s reputation in the theatrical world was such that now his plays could attract the biggest name actors. Tiny Alice starred John Gielgud and Irene Worth, who had played George and Martha in the London production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and was directed by Schneider. However, Tiny Alice did not fare much better than The Ballad of the Sad Cafe, either critically, though it did win the New York Drama Critics’ award, or commercially, running for only 167 performances. After a number of perplexed reviews and diminishing audiences, Albee called a press conference at the theater to offer his explanation of what Tiny Alice was about and to assert that audiences were not confused until the critics told them they should be.

In 1965 Albee’s mother suffered a heart attack, moving him to contact her after almost twenty years of estrangement. He began a relationship with her that lasted until her death twenty years later. They did not grow close emotionally, despite seeing each other regularly at the openings of his plays or visits to his Montauk house, but it did prove beneficial to Albee at least professionally when he would later write Three Tall Women based upon stories his mother told him about her life.

His next project, Malcolm, was adapted from the James Purdy novel of the same title. Opening in January 1966, it closed after only seven performances, his third commercial failure in a row. Later in the same year Albee was hired as a “script doctor” for a musical adaptation of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, but with only one week to revamp the book he could not change its fate, which was to close during previews.

After a string of disappointments, Albee’s career took an upswing with his third original play, A Delicate Balance, which won him his first Pulitzer Prize in drama, though it had a limited run of only 132 performances beginning in September 1966. A Delicate Balance starred Jessica Tandy and her husband Hume Cronyn as Agnes and Tobias, an upper-class couple bearing a resemblance to Albee’s adoptive parents. The autobiographical origin of the play is further evidenced by the similarity between Agnes’ alcoholic sister Claire and Albee’s Aunt Jane, as well as Julia, Agnes and Tobias’ grown daughter, who resembles one of Albee’s cousins. The reviews of A Delicate Balance were mixed, as always, mostly because critics found the unexplained terror of Harry and Edna implausible, and some believed the Pulitzer was an attempt to make up for not having awarded it to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. However, the success of the 1996 revival, winning Tony awards for best play, director, and actor, confirmed the acclamation of the original production. A Delicate Balance was filmed in 1973 with an impressive cast: Katherine Hepburn, Paul Scofield, Kate Reid, Lee Remick, and Joseph Cotton; Tony Richardson was the director. As with the film of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Albee thinks aspects of it are interesting but again laments the missing humor.

By this point in his career Albee had written at least one play a year and had it produced every year since 1959. The 1967 project was Everything in the Garden, his third adaptation, though he had not planned to write another adaptation at this time. His production team had intended to bring British playwright Giles Cooper’s play to New York, revising it only with an American setting. In working on it, however, Albee found himself rewriting so much of it that he eventually felt it had become his own play. Everything in the Garden ran for 84 performances and was mostly panned by critics.

Albee’s next stage venture was no more commercially or critically successful than his adaptations, but it spoke volumes of his integrity as a theatre artist. Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung are two interrelated plays that perhaps show that Albee was influenced by Beckett’s later works, which were shorter and more abstract than his earlier ones. Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung are experiments in non-mimetic and non-narrative theatre and drama. Critics and audiences were, as would be expected, perplexed, and the 1968 production closed after twelve performances, but scholars have taken interest in this experimental work exhibiting Albee’s aesthetic courage. More than any other play of Albee’s Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung show the influence of his ex-partner William Flanagan, who was a composer and the leader of a coterie of musical artists with whom Albee socialized when he first came to Greenwich Village. It is ironic, then, that shortly after Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung were produced Flanagan suffered a drug-and-alcohol-induced heart attack and died. Although it had been ten years since Albee and Flanagan separated, the playwright had continued to send the composer drafts of his plays for comment. The following year Albee sponsored a memorial for Flanagan and announced that he would establish a writers’ colony in Montauk to be named the William Flanagan Memorial Creative Persons Center. It would be a place where writers, musicians, and artists could come for a month in the summer to work on their projects; the colony is still in operation more than forty years later, and is now known as the Edward Albee Foundation.

The death of Flanagan perhaps also inspired Albee’s next play, All Over, which has as its subject the gathering of family and friends around a wealthy man on his deathbed. Unlike Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, All Over is conventionally realistic theatre and drama; it nevertheless closed after 42 performances and was nominated for only one Tony award for best supporting actress.

Originally, All Over was titled “Death” and was conceived along with a companion play to be called “Life.” After numerous revisions, “Life” appeared on Broadway in 1975 under the title Seascape. Although it was no more commercially successful than most of his plays following Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, running for only 65 performances, it did win him his second Pulitzer Prize. Seascape was also a significant step in Albee’s career because it was the first time that he directed the original production of one of his plays. At this time Albee entered into what would be the longest and most stable relationship of his life. After breaking up with William Pennington in 1971, Albee met Jonathon Thomas, a Canadian artist, and not long after they began living together; they remained a couple until Thomas’ death in 2005. Albee credits Thomas with saving him from drinking himself to death, a problem that at times during the Sixties and Seventies was out of control and may have been a factor in his professional decline. At the end of 1975 Albee fulfilled a lifelong dream: he had a poem published in The New Yorker. In 1976 he directed a Broadway revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? starring Colleen Dewhurst, who had previously appeared in two of his plays (The Ballad of the Sad Cafe and All Over). According to Gussow, the reviews for this production were the “closest Albee has come to a unanimously favorable press.” In 1977 he bought a loft in Tribeca and redecorated it with his growing collection of paintings and sculpture. 1977 also saw the American debut of two short plays, Listening and Counting the Ways, having had their world premier in England, since Listening was commissioned by the BBC as a radio drama and Counting the Ways was written as a curtain raiser.

In 1980 Albee returned to the full-length form with The Lady from Dubuque, which reportedly stems from an idea he had in 1960 for a play called The Substitute Speaker. A later inspiration was reading Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s book On Death and Dying. The title of his new play was another allusion to The New Yorker; the original editor, Harold Ross, had described the magazine as not being written for the little old lady from Dubuque, by which he meant a provincial, unsophisticated reader.

The Lady from Dubuque closed after only 12 performances, the first of three commercial and critical failures during the Eighties that would in effect banish Albee from Broadway and the New York theatre scene for a decade. The second was an adaptation of the famous Vladimir Nabokov novel Lolita in 1981. According to Albee, between the Nabokov family, the producers, and the actor playing Humbert Humbert making changes in the script almost daily through rehearsal, what was performed eleven times on stage was not his work; he considers the original draft of a two-part version to be his Lolita, but that was not published. Faring even worse than Lolita, his original play The Man Who Had Three Arms opened first in Chicago in 1982 and then in New York in 1983, but received scathing reviews and closed after 16 performances.

Finding the Sun, written in 1983 on commission from the University of Northern Colorado and first staged there directed by the author, already showed signs of Albee’s comeback. Finding the Sun did not have its New York premiere until 1994 during the Edward Albee season at the Signature Theatre Company where it appeared in a limited run along with The Sandbox and Box under the title Sand. From the perspective of Albee’s career overall, Finding the Sun is significant in that it was his first play to include gay (or, at least, bisexual) characters whose sexuality is an explicit issue. Albee has said that he has never denied being gay but he has not been compelled to write about gay characters and issues except in Finding the Sun (and The Goat, written after this statement). He has stated that there are gay writers and writers who happen to be gay, and that he belongs to the latter category.

In 1984 and 1985 Albee wrote two short plays which have never been published or produced in New York, Walking and Envy, but were performed once each at, respectively, the University of California, Irvine and McCarter Theater in Princeton, New Jersey. The McCarter Theatre was also the site of the U.S. premiere of Marriage Play, commissioned by the English Theater in Vienna where it had its world premiere in June 1987. It was the opening production of the Signature Theatre Albee season in the fall of 1993, but was not well received by critics. Marriage Play was also produced at the Alley Theatre in Houston, where Albee was a writer in residence at the University of Houston for many years, teaching a course in playwriting and occasionally directing his or others’ plays. The Alley Theatre commissioned The Lorca Play, about the Spanish playwright Frederico Garcia Lorca, which Albee wrote and directed there in 1992, but it has not been produced in New York or published.

In 1989 Albee’s mother died, which was a significant event in more ways than one. First, he learned that she had changed her will so that he was no longer the primary beneficiary as he had been after their reconciliation. It was not that he needed the money, but Albee saw this as a final rejection, probably caused by his mother’s refusal to accept his homosexuality. Second, Albee found his adoption papers in her personal possessions, revealing his birth-name and a few details of his abandonment. Third, and most importantly, Albee felt free and perhaps compelled to write about his adoptive family, not to take revenge, since that would be pointless with both of his parents dead, but as an exorcism. He began writing his most autobiographical play in 1990, finished it at the end of the year, and directed its world premiere in Vienna mid-1991. Three Tall Women had its U.S. premiere in Woodstock, New York in 1992, then opened Off-Broadway in January of 1994.

Three Tall Women was a phenomenal success. Directed by Laurence Sacharow and starring Myra Carter and Marion Seldes, it ran for 582 performances, won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, the Pulitzer Prize (Albee’s third), and was hailed as the second coming of Edward Albee by the critics—even those who had condemned his plays in the past. The London production of Three Tall Women was also very successful, winning Dame Maggie Smith and Albee the Evening Standard Awards for best actress and play respectively. In 1994 he was given an Obie Award for Sustained Achievement in the American Theatre.

The rest of the Nineties proved as productive if not as successful for Albee. The Signature Theatre’s Albee season culminated with Fragments, a full-length play commissioned by Ensemble Theater of Cincinnati, where it had its premiere in 1993.

In 1996 A Delicate Balance was revived successfully, the first Broadway production of an Albee play in 13 years; it ran for a modest 186 performances and won Tony awards for best revival, direction, and actor (George Grizzard, who originated the role of Nick in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?). The London production of A Delicate Balance was also successful. Later that year at the Kennedy Center Honors in Washington D.C. Albee was feted by President Clinton and friends and colleagues in the theatrical profession.

In 1998 Albee’s The Play About the Baby, premiered in London to mixed reviews, of course. The American premiere occurred at the Alley Theatre in Houston in April 2000; its New York premiere was in 2001. In 2002 Albee’s The Goat, or Who is Sylvia? opened starring Bill Pullman and Mercedes Ruehl with great controversy, given its taboo subject matter. But it won the Tony Award for best new play and continued its 309-performance run with Bill Irwin and Sally Field in the lead roles.

Since The Goat, Albee has had three plays produced in New York: Occupant (2008) starring Mercedes Ruehl (originally staged in 2002 with Anne Bancroft but never opened); At Home at the Zoo (2007, as Peter and Jerry)—a combination of The Zoo Story and a new act, Homelife, to form a two-act play—starring Bill Pullman, Dallas Roberts, and Johanna Day; and Me, Myself, and I (2010), starring Elizabeth Ashley and Brian Murray (American premiere McCarter Theatre 2008 with Tyne Daly).

After open-heart surgery in 2012, Albee’s health continued to decline. He died September 16, 2016 in his Montauk home. His will made the Edward Albee Foundation the beneficiary; it also ordered all of his unfinished play manuscripts to be destroyed. Until the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020, his plays continued to be performed around the world. A Broadway revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? starring Laurie Metcalf and Rupert Everett was scheduled for spring 2020 but was cancelled. Once theaters can reopen, we have no doubt Edward Albee’s plays will be frequently performed by professional, collegiate, and amateur theater organizations.

Reference: Mel Gussow. Edward Albee: A Singular Journey: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999.